Oldest Message in Bottle: Behind History's Famous Floating Notes

Ensconced in a plain glass bottle, the scrap of paper drifted in the North Sea for 98 years. But when a Scottish skipper pulled it from his nets near the Shetland Islands last April, he didn't find a lovelorn note or marooned sailor's SOS.

Ensconced in a plain glass bottle, the scrap of paper drifted in the North Sea for 98 years. But when a Scottish skipper pulled it from his nets near the Shetland Islands last April, he didn't find a lovelorn note or marooned sailor's SOS.

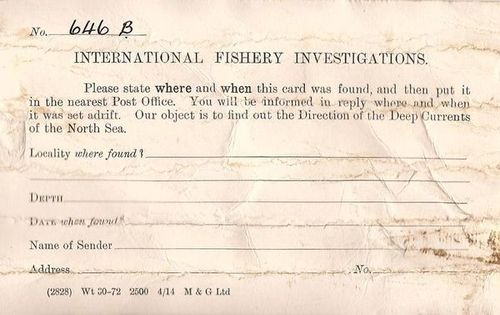

"Please state where and when this card was found, and then put it in the nearest Post Office," read the message. "You will be informed in reply where and when it was set adrift. Our object is to find out the direction of the deep currents of the North Sea."

Sorry, romantics.

The message in a bottle found by Andrew Leaper—certified by Guinness World Records on August 30 as the oldest ever recovered—belonged to a century-old science experiment. To study local ocean currents, Capt. C. Hunter Brown of the Glasgow School of Navigation set bottle number 646B adrift, along with 1,889 others, on June 10, 1914.

"Drift bottles gave oceanographers at the start of the last century important information that allowed them to create pictures of the patterns of water circulation in the seas around Scotland," Marine Scotland Science's Bill Turrell explained in a statement.

Turrell's Aberdeen-based government agency still keeps and updates Captain Brown's log. According to Turrell, Leaper's discovery—plucked just 9 miles (15 kilometers) from where Brown released it—is the 315th bottle recovered from that experiment. Each one, Turrell explained, was "specially weighted to bob along the seabed," hopefully to be scooped up by a trawler or to eventually wash up on shore.

Oddly enough, the previous record—a message in a bottle dating to 1917—was set in 2006 by Mark Anderson, a friend of Leaper's who was sailing the same ship, the Copious. "It was an amazing coincidence," Leaper said in a statement. "It's like winning the lottery twice."

Current History

Of course, people have been putting messages in bottles for a lot longer than 98 years. Around 310 B.C., the Greek philosopher Theophrastus plopped sealed bottles in the sea to prove that the Mediterranean was formed by the inflowing Atlantic. (There's no record showing that he ever received a response.)

In the 16th century, Queen Elizabeth I of England—thinking some bottles might contain secret messages sent home by British spies or fleets—appointed an "Uncorker of Ocean Bottles," making it a capital crime for anyone else to open one.

And in the 18th century, a treasure-hunting seaman from Japan named Chunosuke Matsuyama, shipwrecked on a South Pacific island with 43 shipmates, carved a message into coconut wood, put it in a bottle, and set it adrift. It was found in 1935—supposedly in the same village where Matsuyama was born.

In the 20th century, doomed World War I soldiers used bottles to send last messages to loved ones. And in 1915, a passenger on the torpedoed Lusitaniatossed a poignant note that read, according to one report, "Still on deck with a few people. The last boats have left. We are sinking fast. Some men near me are praying with a priest. The end is near. Maybe this note will—"

Set Adrift for Science

Today drift bottles are still used by oceanographers studying global currents. In 2000 Eddy Carmack, a climate researcher at Canada's Institute of Ocean Science, started the Drift Bottle Project, initially to study currents around northern North America.

In the past 12 years, he and his colleagues have launched some 6,400 bottled messages from ships around the world. Of those, 264—about 4 percent—have been found and reported.

"There have been some amazing paths followed by these bottles," Carmack said.

Three that were dropped into the Beaufort Sea, above northern Alaska and northwestern Canada, became frozen in sea ice, he said. Five years later, melting Arctic ice had flushed the bottles all the way to northern Europe. (See"Arctic Sea Ice Hits Record Low—Extreme Weather to Come?") Another bottle circled Antarctica one and a half times before it wound up on the Australian island of Tasmania. Some have made it from Mexico to the Philippines. And others have demonstrated that oil spills and debris from development in Canada's Labrador Sea and Baffin Bay could end up on Irish, French, Scottish, and Norwegian beaches.

But there's more to the project than science, Carmack said. "The main thing about this study is that it connects people with the currents of the ocean," he said. "We find that we are only a bottle drop away from our neighbors around the world."

One Man's Message-in-a-Bottle Obsession

Sean Bercaw agrees.

A captain and teacher in Connecticut, Bercaw has been obsessed with drift bottles since the early 1970s, when he and his parents sailed around the world on a 38-foot (12-meter) ketch called Natasha. As a 10-year-old, Bercaw dropped 40 bottles over the side—"my parents didn't drink, so I had to scrounge bottles from behind bars in ports of call"—and received two responses.

Twenty-five years later, he began the project anew. Today he's cast more than 250 bottles into the sea and received responses from about 50.

"I've had 7-year-old kids and people in their 70s find my bottles and write back," he said. "Once I dropped two off the East Coast, a day apart. Both made it to France. But I heard about one just a year and a half later. The other took ten years."

Bercaw favors tightly corked wine bottles ("they float best") and seals his handwritten messages in plastic bags, to waterproof them further. He explained that water pressure helps keep a bottle sealed, so one that drifts well below the surface—like the 98-year-old bottle found in Scotland, which Bercaw suspects was long lodged on the seafloor—has a stronger seal than one floating higher on the waves.

"One of the things I find fascinating about messages in bottles is how they bring things together," Bercaw said. "A lot of times in our society, it's either/or—there's science, and there's humanities. But with drift bottles it's both: You learn about ocean currents, but the messages themselves are so human."

They also bridge oceans of time—and technology.

"Once this guy in the Bahamas called me," Bercaw remembered, "and he said to me, over a new satellite cell phone, 'Hey, I found your message in an old bottle!'"

Source: news.nationalgeographic.com

(25.09.2012)